Security

Introduction

This chapter of the Web Almanac looks at the current status of security on the web. With security and privacy becoming increasingly more important online there has been an increase in the availability of features to protect site operators and users. We’re going to look at the adoption of these new features across the web.

Transport Layer Security

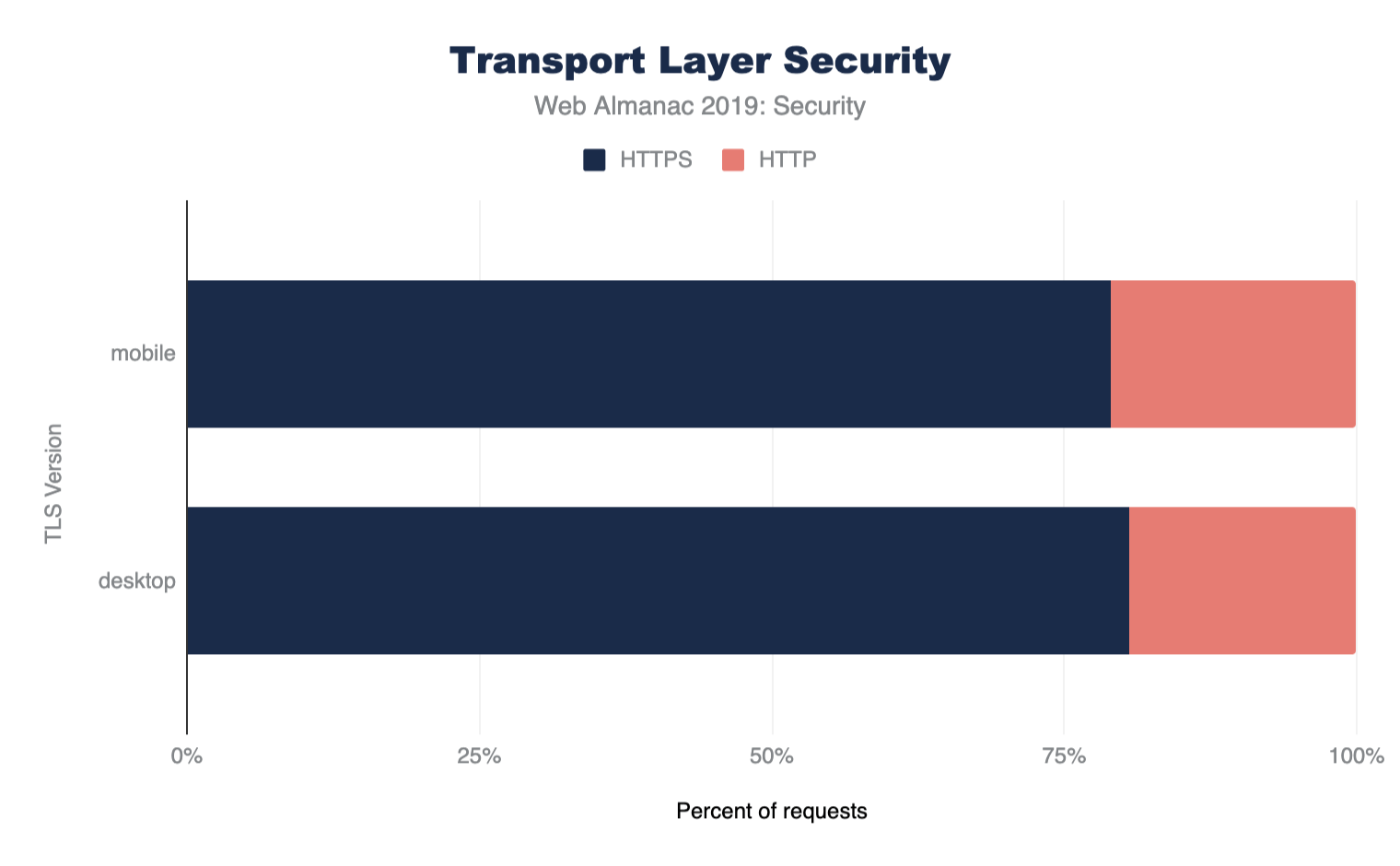

Perhaps the largest push to increasing security and privacy online we’re seeing at present is the widespread adoption of Transport Layer Security (TLS). TLS (or the older version, SSL) is the protocol that gives us the ’S’ in HTTPS and allows secure and private browsing of websites. Not only are we seeing a great increase in the use of HTTPS across the web, but also an increase in more modern versions of TLS like TLSv1.2 and TLSv1.3, which is also important.

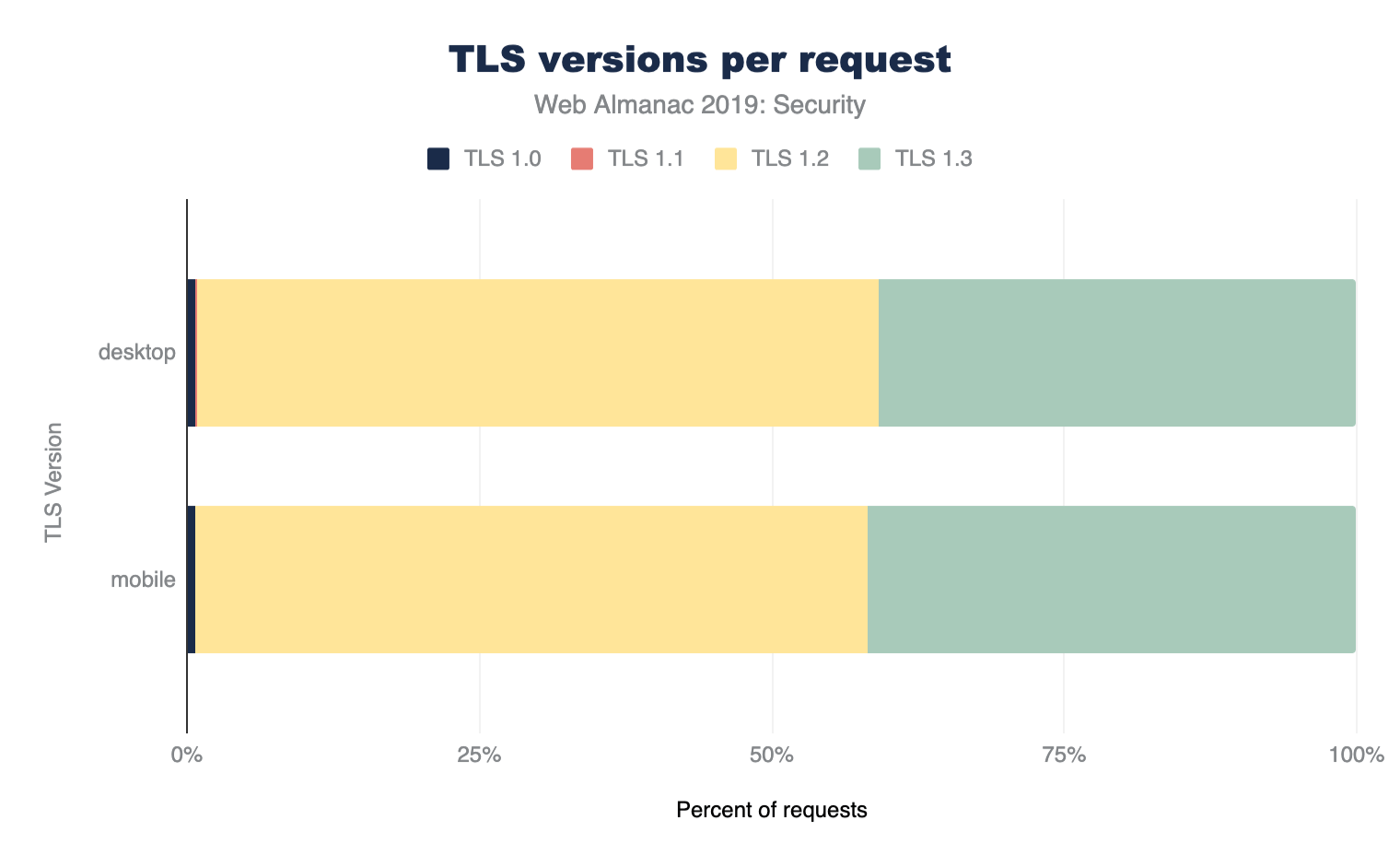

Protocol versions

Figure 8.2 shows the support for various protocol versions. Use of legacy TLS versions like TLSv1.0 and TLSv1.1 is minimal and almost all support is for the newer TLSv1.2 and TLSv1.3 versions of the protocol. Even though TLSv1.3 is still very young as a standard (TLSv1.3 was only formally approved in August 2018), over 40% of requests using TLS are using the latest version!

This is likely due to many sites using requests from the larger players for third-party content. For example, any sites load Google Analytics, Google AdWords, or Google Fonts and these large players like Google are typically early adopters for new protocols.

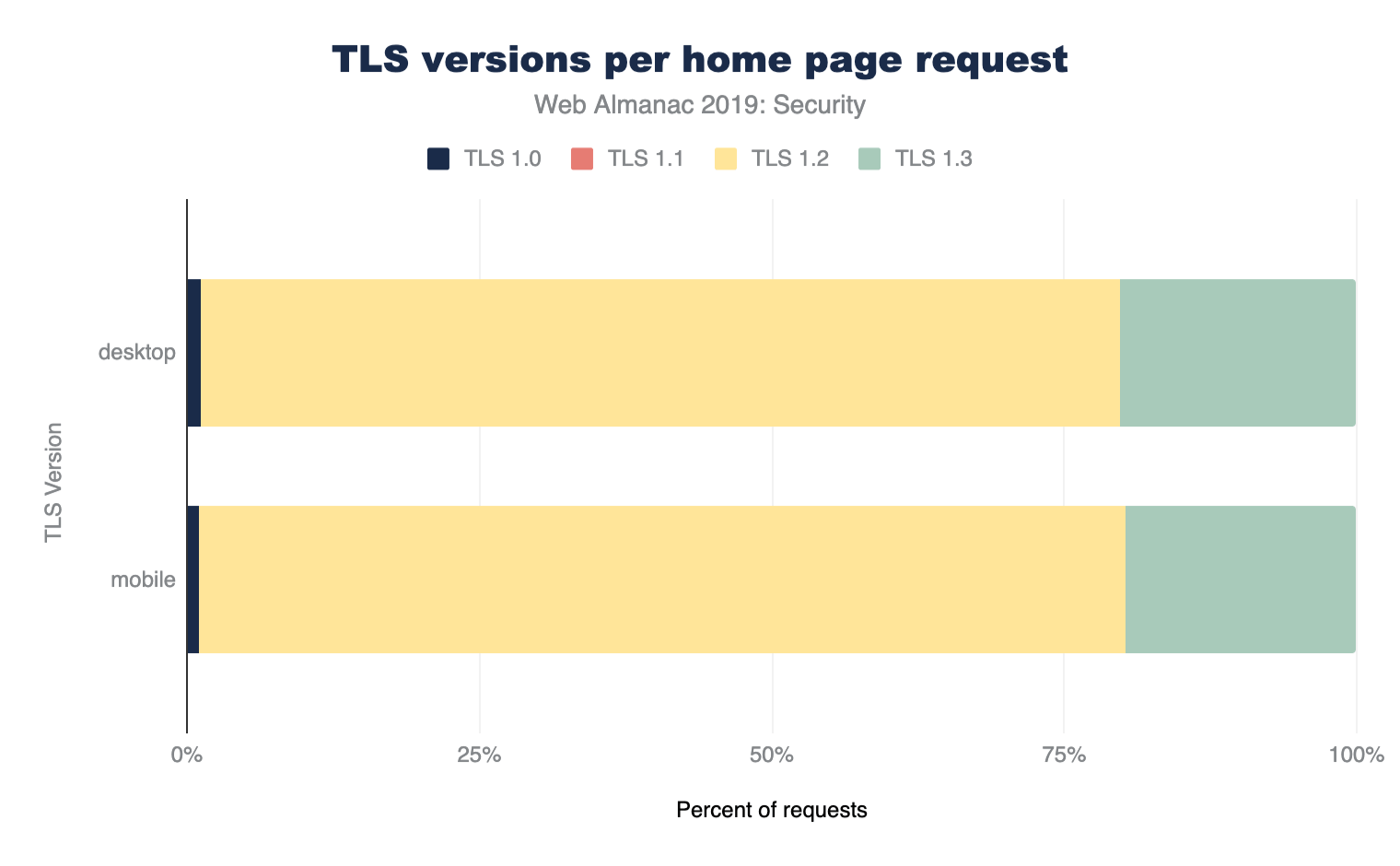

If we look at just home pages, and not all the other requests made on sites, then the usage of TLS is considerably as expected, though still quite high which is likely due to CMS sites like Wordpress and CDNs:

On the other hand, the methodology used by the Web Almanac will also under-report usage from large sites, as their sites themselves will likely form a larger volume of internet traffic in the real world, yet are crawled only once for these statistics.

Certificate Authorities

Of course, if we want to use HTTPS on our website then we need a certificate from a Certificate Authority (CA). With the increase in the use of HTTPS comes the increase in use of CAs and their products/services. Here are the top ten certificate issuers based on the volume of TLS requests that use their certificate.

| Issuing Certificate Authority | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| Google Internet Authority G3 | 19.26% | 19.68% |

| Let’s Encrypt Authority X3 | 10.20% | 9.19% |

| DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA | 9.83% | 9.26% |

| DigiCert SHA2 Secure Server CA | 7.55% | 8.72% |

| GTS CA 1O1 | 7.87% | 8.43% |

| DigiCert SHA2 Secure Server CA | 7.55% | 8.72% |

| COMODO RSA Domain Validation Secure Server CA | 6.29% | 5.79% |

| Go Daddy Secure Certificate Authority - G2 | 4.84% | 5.10% |

| Amazon | 4.71% | 4.45% |

| COMODO ECC Domain Validation Secure Server CA 2 | 3.22% | 2.75% |

As previously discussed, the volume for Google likely reflects repeated use of Google Analytics, Google Adwords, or Google Fonts on other sites.

The rise of Let’s Encrypt has been meteoric after their launch in early 2016, since then they’ve become one of the top certificate issuers in the world. The availability of free certificates and the automated tooling has been critically important to the adoption of HTTPS on the web. Let’s Encrypt certainly had a significant part to play in both of those.

The reduced cost has removed the barrier to entry for HTTPS, but the automation Let’s Encrypt uses is perhaps more important in the long run as it allows shorter certificate lifetimes which has many security benefits.

Authentication key type

Alongside the important requirement to use HTTPS is the requirement to also use a good configuration. With so many configuration options and choices to make, this is a careful balance.

First of all, we’ll look at the keys used for authentication purposes. Traditionally certificates have been issued based on keys using the RSA algorithm, however a newer and better algorithm uses ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) which allows the use of smaller keys that demonstrate better performance than their RSA counterparts. Looking at the results of our crawl we still see a large % of the web using RSA.

| Key Type | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| RSA Keys | 48.67% | 58.8% |

| ECDA Keys | 21.47% | 26.41% |

Whilst ECDSA keys are stronger, which allows the use of smaller keys and demonstrate better performance than their RSA counterparts, concerns around backwards compatibility, and complications in supporting both in the meantime, do prevent some website operators from migrating.

Forward secrecy

Forward secrecy is a property of some key exchange mechanisms that secures the connection in such a way that it prevents each connection to a server from being exposed even in case of a future compromise of the server’s private key. This is well understood within the security community as desirable on all TLS connections to safeguard the security of those connections. It was introduced as an optional configuration in 2008 with TLSv1.2 and has become mandatory in 2018 with TLSv1.3 requiring the use of Forward Secrecy.

Looking at the % of TLS requests that provide Forward Secrecy, we can see that support is tremendous. 96.92% of Desktop and 96.49% of mobile requests use Forward secrecy. We’d expect that the continuing increase in the adoption of TLSv1.3 will further increase these numbers.

Cipher suites

TLS allows the use of various cipher suites - some newer and more secure, and some older and insecure. Traditionally newer TLS versions have added cipher suites but have been reluctant to remove older cipher suites. TLSv1.3 aims to simplify this by offering a reduced set of ciphers suites and will not permit the older, insecure, cipher suites to be used. Tools like SSL Labs allow the TLS setup of a website (including the cipher suites supported and their preferred order) to be easily seen, which helps drive better configurations. We can see that the majority of cipher suites negotiated for TLS requests were indeed excellent:

| Cipher Suite | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

AES_128_GCM |

75.87% | 76.71% |

AES_256_GCM |

19.73% | 18.49% |

AES_256_CBC |

2.22% | 2.26% |

AES_128_CBC |

1.43% | 1.72% |

CHACHA20_POLY1305 |

0.69% | 0.79% |

3DES_EDE_CBC |

0.06% | 0.04% |

It is positive to see such wide stream use of GCM ciphers since the older CBC ciphers are less secure. CHACHA20_POLY1305 is still an niche cipher suite, and we even still have a very small use of the insecure 3DES ciphers.

It should be noticed that these were the cipher suites used for the crawl using Chrome, but sites will likely also support other cipher suites as well for older browsers. Other sources, for example SSL Pulse, can provide more detail on the range of all cipher suites and protocols supported.

Mixed content

Most sites on the web originally existed as HTTP websites and have had to migrate their site to HTTPS. This ’lift and shift’ operation can be difficult and sometimes things get missed or left behind. This results in sites having mixed content, where their pages load over HTTPS but something on the page, perhaps an image or a style, is loaded over HTTP. Mixed content is bad for security and privacy and can be difficult to find and fix.

| Mixed Content Type | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| Pages with Any Mixed Content | 16.27% | 15.37% |

| Pages with Active Mixed Content | 3.99% | 4.13% |

We can see that around 20% of sites across mobile (645,485 sites) and desktop (594,072 sites) present some form of mixed content. Whilst passive mixed content, something like an image, is less dangerous, we can still see that almost a quarter of sites with mixed content have active mixed content. Active mixed content, like JavaScript, is more dangerous as an attacker can insert their own hostile code into a page easily.

In the past web browsers have allowed passive mixed content and flagged it with a warning but blocked active mixed content. More recently however, Chrome announced it intends to improve here and as HTTPS becomes the norm it will block all mixed content instead.

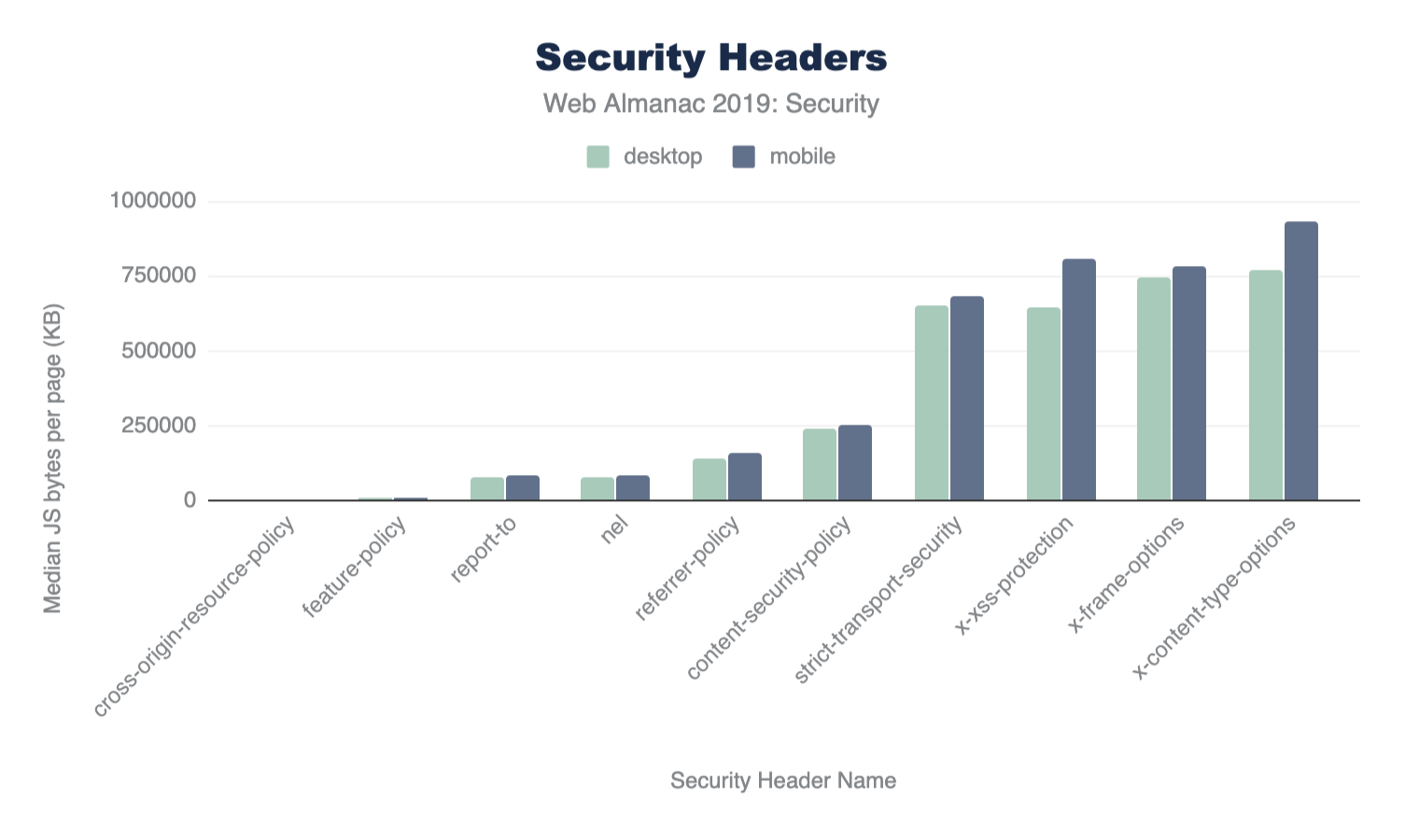

Security headers

Many new and recent features for site operators to better protect their users have come in the form of new HTTP response headers that can configure and control security protections built into the browser. Some of these features are easy to enable and provide a huge level of protection whilst others require a little more work from site operators. If you wish to check if a site is using these headers and has them correctly configured, you can use the Security Headers tool to scan it.

HTTP Strict Transport Security

The HSTS header allows a website to instruct a browser that it should only ever communicate with the site over a secure HTTPS connection. This means that any attempts to use a http:// URL will automatically be converted to https:// before a request is made. Given that over 40% of requests were capable of using TLS, we see a much lower % of requests instructing the browser to require it.

| HSTS Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

max-age |

14.80% | 12.81% |

includeSubDomains |

3.86% | 3.29% |

preload |

2.27% | 1.99% |

Less than 15% of mobile and desktop pages are issuing a HSTS with a max-age directive. This is a minimum requirement for a valid policy. Fewer still are including subdomains in their policy with the includeSubDomains directive and even fewer still are HSTS preloading. Looking at the median value for a HSTS max-age, for those that do use this, we can see that on both desktop and mobile it is 15768000, a strong configuration representing half a year (60 x 60 x 24 x 365/2).

| Client | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percentile | Desktop | Mobile |

| 10 | 300 | 300 |

| 25 | 7889238 | 7889238 |

| 50 | 15768000 | 15768000 |

| 75 | 31536000 | 31536000 |

| 90 | 63072000 | 63072000 |

max-age policy by percentile.

HSTS preloading

With the HSTS policy delivered via an HTTP response Header, when visiting a site for the first time a browser will not know whether a policy is configured. To avoid this Trust On First Use problem, a site operator can have the policy preloaded into the browser (or other user agents) meaning you are protected even before you visit the site for the first time.

There are a number of requirements for preloading, which are outlined on the HSTS preload site. We can see that only a small number of sites, 0.31% on desktop and 0.26% on mobile, are eligible according to current criteria. Sites should ensure they have fully transitions all sites under their domain to HTTPS before submitting to preload the domain or they risk blocking access to HTTP-only sites.

Content Security Policy

Web applications face frequent attacks where hostile content finds its way into a page. The most worrisome form of content is JavaScript and when an attacker finds a way to insert JavaScript into a page, they can launch damaging attacks. These attacks are known as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and Content Security Policy (CSP) provides an effective defense against these attacks.

CSP is an HTTP header (Content-Security-Policy) published by a website which tells the browser rules around content allowed on a site. If additional content is injected into the site due to a security flaw, and it is not allowed by the policy, the browser will block it from being used. Alongside XSS protection, CSP also offers several other key benefits such as making migration to HTTPS easier.

Despite the many benefits of CSP, it can be complicated to implement on websites since its very purpose is to limit what is acceptable on a page. The policy must allow all content and resources you need and can easily get large and complex. Tools like Report URI can help you analyze and build the appropriate policy.

We find that only 5.51% of desktop pages include a CSP and only 4.73% of mobile pages include a CSP, likely due to the complexity of deployment.

Hash/nonce

A common approach to CSP is to create an allowlist of 3rd party domains that are permitted to load content, such as JavaScript, into your pages. Creating and managing these lists can be difficult so hashes and nonces were introduced as an alternative approach. A hash is calculated based on contents of the script so if this is published by the website operator and the script is changed, or another script is added, then it will not match the hash and will be blocked. A nonce is a one-time code (which should be changed each time the page is loaded to prevent it being guessed) which is allowed by the CSP and which the script is tagged with. You can see an example of a nonce on this page by viewing the source to see how Google Tag Manager is loaded.

Of the sites surveyed only 0.09% of desktop pages use a nonce source and only 0.02% of desktop pages use a hash source. The number of mobile pages use a nonce source is slightly higher at 0.13% but the use of hash sources is lower on mobile pages at 0.01%.

strict-dynamic

The proposal of strict-dynamic in the next iteration of CSP further reduces the burden on site operators for using CSP by allowing an approved script to load further script dependencies. Despite the introduction of this feature, which already has support in some modern browsers, only 0.03% of desktop pages and 0.1% of mobile pages include it in their policy.

trusted-types

XSS attacks come in various forms and Trusted-Types was created to help specifically with DOM-XSS. Despite being an effective mechanism, our data shows that only 2 mobile and desktop pages use the Trusted-Types directive.

unsafe inline and unsafe-eval

When a CSP is deployed on a page, certain unsafe features like inline scripts or the use of eval() are disabled. A page can depend on these features and enable them in a safe fashion, perhaps with a nonce or hash source. Site operators can also re-enable these unsafe features with unsafe-inline or unsafe-eval in their CSP though, as their names suggest, doing so does lose much of the protections that CSP gives you. Of the 5.51% of desktop pages that include a CSP, 33.94% of them include unsafe-inline and 31.03% of them include unsafe-eval. On mobile pages we find that of the 4.73% that contain a CSP, 34.04% use unsafe-inline and 31.71% use unsafe-eval.

upgrade-insecure-requests

We mentioned earlier that a common problem that site operators face in their migration from HTTP to HTTPS is that some content can still be accidentally loaded over HTTP on their HTTPS page. This problem is known as mixed content and CSP provides an effective way to solve this problem. The upgrade-insecure-requests directive instructs a browser to load all subresources on a page over a secure connection, automatically upgrading HTTP requests to HTTPS requests as an example. Think of it like HSTS for subresources on a page.

We showed earlier in Figure 8.7 that, of the HTTPS pages surveyed on the desktop, 16.27% of them loaded mixed-content with 3.99% of pages loading active mixed-content like JS/CSS/fonts. On mobile pages we see 15.37% of HTTPS pages loading mixed-content with 4.13% loading active mixed-content. By loading active content such as JavaScript over HTTP an attacker can easily inject hostile code into the page to launch an attack. This is what the upgrade-insecure-requests directive in CSP protects against.

The upgrade-insecure-requests directive is found in the CSP of 3.24% of desktop pages and 2.84% of mobile pages, indicating that an increase in adoption would provide substantial benefits. It could be introduced with relative ease, without requiring a fully locked-down CSP and the complexity that would entail, by allowing broad categories with a policy like below, or even including unsafe-inline and unsafe-eval:

Content-Security-Policy: upgrade-insecure-requests; default-src https:

frame-ancestors

Another common attack known as clickjacking is conducted by an attacker who will place a target website inside an iframe on a hostile website, and then overlay hidden controls and buttons that they are in control of. Whilst the X-Frame-Options header (discussed below) originally set out to control framing, it wasn’t flexible and frame-ancestors in CSP stepped in to provide a more flexible solution. Site operators can now specify a list of hosts that are permitted to frame them and any other hosts attempting to frame them will be prevented.

Of the pages surveyed, 2.85% of desktop pages include the frame-ancestors directive in CSP with 0.74% of desktop pages setting Frame-Ancestors to 'none', preventing any framing, and 0.47% of pages setting frame-ancestors to 'self', allowing only their own site to frame itself. On mobile we see 2.52% of pages using frame-ancestors with 0.71% setting the value of 'none' and 0.41% setting the value to 'self'.

Referrer Policy

The Referrer-Policy header allows a site to control what information will be sent in the Referer header when a user navigates away from the current page. This can be the source of information leakage if there is sensitive data in the URL, such as search queries or other user-dependent information included in URL parameters. By controlling what information is sent in the Referer header, ideally limiting it, a site can protect the privacy of their visitors by reducing the information sent to 3rd parties.

Note the Referrer Policy does not follow the Referer header’s misspelling which has become a well-known error.

A total of 3.25% of desktop pages and 2.95% of mobile pages issue a Referrer-Policy header and below we can see the configurations those pages used.

| Configuration | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

no-referrer-when-downgrade |

39.16% | 41.52% |

strict-origin-when-cross-origin |

39.16% | 22.17% |

unsafe-url |

22.17% | 22.17% |

same-origin |

7.97% | 7.97% |

origin-when-cross-origin |

6.76% | 6.44% |

no-referrer |

5.65% | 5.38% |

strict-origin |

4.35% | 4.14% |

origin |

3.63% | 3.23% |

Referrer-Policy configuration option usage.

This table shows the valid values set by pages and that, of the pages which use this header, 99.75% of them on desktop and 96.55% of them on mobile are setting a valid policy. The most popular choice of configuration is no-referrer-when-downgrade which will prevent the Referer header being sent when a user navigates from a HTTPS page to a HTTP page. The second most popular choice is strict-origin-when-cross-origin which prevents any information being sent on a scheme downgrade (HTTPS to HTTP navigation) and when information is sent in the Referer it will only contain the origin of the source and not the full URL (for example https://www.example.com rather than https://www.example.com/page/). Details on the other valid configurations can be found in the Referrer Policy specification, though such a high usage of unsafe-url warrants further investigation but is likely to be a third-party component like analytics or advertisement libraries.

Feature Policy

As the web platform becomes more powerful and feature rich, attackers can abuse these new APIs in interesting ways. In order to limit misuse of powerful APIs, a site operator can issue a Feature-Policy header to disable features that are not required, preventing them from being abused.

Here are the 5 most popular features that are controlled with a Feature Policy.

| Feature | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

microphone |

10.78% | 10.98% |

camera |

9.95% | 10.19% |

payment |

9.54% | 9.54% |

geolocation |

9.38% | 9.41% |

gyroscope |

7.92% | 7.90% |

Feature-Policy options used.

We can see that the most popular feature to take control of is the microphone, with almost 11% of desktop and mobile pages issuing a policy that includes it. Delving deeper into the data we can look at what those pages are allowing or blocking.

| Feature | Configuration | Usage |

|---|---|---|

microphone |

none |

9.09% |

microphone |

none |

8.97% |

microphone |

self |

0.86% |

microphone |

self |

0.85% |

microphone |

* |

0.64% |

microphone |

* |

0.53% |

microphone feature.

By far the most common approach here is to block use of the microphone altogether, with about 9% of pages taking that approach. A small number of pages do allow the use of the microphone by their own origin and interestingly, a small selection of pages intentionally allow use of the microphone by any origin loading content in their page.

X-Frame-Options

The X-Frame-Options header allows a page to control whether or not it can be placed in an iframe by another page. Whilst lacking the flexibility of frame-ancestors in CSP, mentioned above, it was effective if you didn’t require fine grained control of framing.

We see that the usage of the X-Frame-Options header is quite high on both desktop (16.99%) and mobile (14.77%) and can also look more closely at the specific configurations used.

| Configuration | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

sameorigin |

84.92% | 83.86% |

deny |

13.54% | 14.50% |

allow-from |

1.53% | 1.64% |

X-Frame-Options configuration used.

It seems that the vast majority of pages restrict framing to only their own origin and the next significant approach is to prevent framing altogether. This is similar to frame-ancestors in CSP where these 2 approaches are also the most common. It should also be noted that the allow-from option, which in theory allow site owners to list the third-party domains allowed to frame was never well supported and has been deprecated.

X-Content-Type-Options

The X-Content-Type-Options header is the most widely deployed Security Header and is also the most simple, with only one possible configuration value nosniff. When this header is issued a browser must treat a piece of content as the MIME Type declared in the Content-Type header and not try to change the advertised value when it infers a file is of a different type. Various security flaws can be introduced if a browser is persuaded to incorrectly sniff the type..

We find that an identical 17.61% of pages on both mobile and desktop issue the X-Content-Type-Options header.

X-XSS-Protection

The X-XSS-Protection header allows a site to control the XSS Auditor or XSS Filter built into a browser, which should in theory provide some XSS protection.

14.69% of Desktop requests, and 15.2% of mobile requests used the X-XSS-Protection header. Digging into the data we can see what the intention for most site operators was in Figure 8.13.

| Configuration | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

1;mode=block |

91.77% | 91.46% |

1 |

5.54% | 5.35% |

0 |

2.58% | 3.11% |

1;report= |

0.12% | 0.09% |

X-XSS-Protection configuration usage.

The value 1 enables the filter/auditor and mode=block sets the protection to the strongest setting (in theory) where any suspected XSS attack would cause the page to not be rendered. The second most common configuration was to simply ensure the auditor/filter was turned on, by presenting a value of 1 and then the 3rd most popular configuration is quite interesting.

Setting a value of 0 in the header instructs the browser to disable any XSS auditor/filter that it may have. Some historic attacks demonstrated how the auditor or filter could be tricked into assisting an attacker rather than protecting the user so some site operators could disable it if they were confident they have adequate protection against XSS in place.

Due to these attacks, Edge retired their XSS Filter, Chrome deprecated their XSS Auditor and Firefox never implemented support for the feature. We still see widespread use of the header at approximately 15% of all sites, despite it being largely useless now.

Report-To

The Reporting API was introduced to allow site operators to gather various pieces of telemetry from the browser. Many errors or problems on a site can result in a poor experience for the user yet a site operator can only find out if the user contacts them. The Reporting API provides a mechanism for a browser to automatically report these problems without any user interaction or interruption. The Reporting API is configured by delivering the Report-To header.

By specifying the header, which contains a location where the telemetry should be sent, a browser will automatically begin sending the data and you can use a 3rd party service like Report URI to collect the reports or collect them yourself. Given the ease of deployment and configuration, we can see that only a small fraction of desktop (1.70%) and mobile (1.57%) sites currently enable this feature. To see the kind of telemetry you can collect, refer to the Reporting API specification.

Network Error Logging

Network Error Logging (NEL) provides detailed information about various failures in the browser that can result in a site being inoperative. Whereas the Report-To is used to report problems with a page that is loaded, the NEL header allows sites to inform the browser to cache this policy and then to report future connection problems when they happen via the endpoint configured in the Reporting-To header above. NEL can therefore be seen as an extension of the Reporting API.

Of course, with NEL depending on the Reporting API, we shouldn’t see the usage of NEL exceed that of the Reporting API, so we see similarly low numbers here too at 1.70% for desktop requests and 1.57% for mobile. The fact these numbers are identical suggest they are being deployed together.

NEL provides incredibly valuable information and you can read more about the type of information in the Network Error Logging specification.

Clear Site Data

With the increasing ability to store data locally on a user’s device, via cookies, caches and local storage to name but a few, site operators needed a reliable way to manage this data. The Clear Site Data header provides a means to ensure that all data of a particular type is removed from the device, though it is not yet supported in all browsers.

Given the nature of the header, it is unsurprising to see almost no usage reported - just 9 desktop requests and 7 mobile requests. With our data only looking at the home page of a site, we’re unlikely to see the most common use of the header which would be on a logout endpoint. Upon logging out of a site, the site operator would return the Clear Site Data header and the browser would remove all data of the indicated types. This is unlikely to take place on the home page of a site.

Cookies

Cookies have many security protections available and whilst some of those are long standing, and have been available for years, some of them are really quite new have been introduced only in the last couple of years.

Secure

The Secure flag on a cookie instructs a browser to only send the cookie over a secure (HTTPS) connection and we find only a small % of sites (4.22% on desktop and 3.68% on mobile) issuing a cookie with the Secure flag set on their home page. This is depressing considering the relative ease with which this feature can be used. Again, the high usage of analytics and advertisement third-party requests, which wish to collect data over both HTTP and HTTPS is likely skewing these numbers and it would be interesting research to see the usage on other cookies, like authentication cookies.

HttpOnly

The HttpOnly flag on a cookie instructs the browser to prevent JavaScript on the page from accessing the cookie. Many cookies are only used by the server so are not needed by the JavaScript on the page, so restricting access to a cookie is a great protection against XSS attacks from stealing the cookie. We find that a much larger % of sites issuing a cookie with this flag on their home page at 24.24% on desktop and 22.23% on mobile.

SameSite

As a much more recent addition to cookie protections, the SameSite flag is a powerful protection against Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks (often also known as XSRF).

These attacks work by using the fact that browsers will typically include relevant cookies in all requests. Therefore, if you are logged in, and so have cookies set, and then visit a malicious site, it can make a call for an API and the browser will “helpfully” send the cookies. Adding the SameSite attribute to a Cookie, allows a website to inform the browser not to send the cookies when calls are issued from third-party sites and hence the attack fails.

Being a recently introduced mechanism, the usage of Same-Site cookies is much lower as we would expect at 0.1% of requests on both desktop and mobile. There are use cases when a cookie should be sent cross-site. For example, single sign-on sites implicitly work by setting the cookie along with an authentication token.

| Configuration | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

strict |

53.14% | 50.64% |

lax |

45.85% | 47.42% |

none |

0.51% | 0.41% |

We can see that of those pages already using Same-Site cookies, more than half of them are using it in strict mode. This is closely followed by sites using Same-Site in lax mode and then a small selection of sites using the value none. This last value is used to opt-out of the upcoming change where browser vendors may implement lax mode by default.

Because it provides much needed protection against a dangerous attack, there are currently indications that leading browsers could implement this feature by default and enable it on cookies even though the value is not set. If this were to happen the SameSite protection would be enabled, though in its weaker setting of lax mode and not strict mode, as that would likely cause more breakage.

Prefixes

Another recent addition to cookies are Cookie Prefixes. These use the name of your cookie to add one of two further protections to those already covered. While the above flags can be accidentally unset on cookies, the name will not change so using the name to define security attributes can more reliably enforce them.

Currently the name of your cookie can be prefixed with either __Secure- or __Host-, with both offering additional security to the cookie.

| No. of Home Pages | % of Home Pages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix value | Desktop | Mobile | Desktop | Mobile |

__Secure- |

640 | 628 | 0.01% | 0.01% |

__Host- |

154 | 157 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

As the figures show, the use of either prefix is incredibly low but as the more relaxed of the two, the __Secure- prefix does see more utilization already.

Subresource Integrity

Another problem that has been on the rise recently is the security of 3rd party dependencies. When loading a script file from a 3rd party, we hope that the script file is always the library that we wanted, perhaps a particular version of jQuery. If a CDN or 3rd party hosting service is compromised, the script files they are hosting could be altered. In this scenario your application would now be loading malicious JavaScript that could harm your visitors. This is what subresource integrity protects against.

By adding an integrity attribute to a script or link tag, a browser can integrity check the 3rd party resource and reject it if it has been altered, in a similar manner that CSP hashes described above are used.

<script

src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.4.1.min.js"

integrity="sha256-CSXorXvZcTkaix6Yvo6HppcZGetbYMGWSFlBw8HfCJo="

crossorigin="anonymous"></script>With only 0.06% (247,604) of desktop pages and 0.05% (272,167) of mobile pages containing link or script tags with the integrity attribute set, there’s room for a lot of improvement in the use of SRI. With many CDNs now providing code samples that include the SRI integrity attribute we should see a steady increase in the use of SRI.

Conclusion

As the web grows in capabilities and allows access to more and more sensitive data, it becomes increasingly important for developers to adopt web security features to protect their applications. The security features reviewed in this chapter are defenses built into the web platform itself, available to every web author. However, as a review of the study results in this chapter shows, the coverage of several important security mechanisms extends only to a subset of the web, leaving a significant part of the ecosystem exposed to security or privacy bugs.

Encryption

In the recent years, the web has made the most progress on the encryption of data in transit. As described in the TLS section section, thanks to a range of efforts from browser vendors, developers and Certificate Authorities such as Let’s Encrypt, the fraction of the web using HTTPS has steadily grown. At the time of writing, the majority of sites are available over HTTPS, ensuring confidentiality and integrity of traffic. Importantly, over 99% of websites which enable HTTPS use newer, more secure versions of the TLS protocol (TLSv1.2 and TLSv1.3). The use of strong cipher suites such as AES in GCM mode is also high, accounting for over 95% of requests on all platforms.

At the same time, gaps in TLS configurations are still fairly common. Over 15% of pages suffer from mixed content issues, resulting in browser warnings, and 4% of sites contain active mixed content, blocked by modern browsers for security reasons. Similarly, the benefits of HTTP Strict Transport Security only extend to a small subset of major sites, and the majority of websites don’t enable the most secure HSTS configurations and are not eligible for HSTS preloading. Despite progress in HTTPS adoption, a large number of cookies is still set without the Secure flag; only 4% of home pages that set cookies prevent them from being sent over unencrypted HTTP.

Defending against common web vulnerabilities

Web developers working on sites with sensitive data often enable opt-in web security features to protect their applications from XSS, CSRF, clickjacking, and other common web bugs. These issues can be mitigated by setting a number of standard, broadly supported HTTP response headers, including X-Frame-Options, X-Content-Type-Options, and Content-Security-Policy.

In large part due to the complexity of both the security features and web applications, only a minority of websites currently use these defenses, and often enable only those mechanisms which do not require significant refactoring efforts. The most common opt-in application security features are X-Content-Type-Options (enabled by 17% of pages), X-Frame-Options (16%), and the deprecated X-XSS-Protection header (15%). The most powerful web security mechanism—Content Security Policy—is only enabled by 5% of websites, and only a small subset of them (about 0.1% of all sites) use the safer configurations based on CSP nonces and hashes. The related Referrer-Policy, aiming to reduce the amount of information sent to third parties in the Referer headers is similarly only used by 3% of websites.

Modern web platform defenses

In the recent years, web browsers have implemented powerful new mechanisms which offer protections from major classes of vulnerabilities and new web threats; this includes Subresource Integrity, SameSite cookies, and cookie prefixes.

These features have seen adoption only by a relatively small number of websites; their total coverage is generally well below 1%. The even more recent security mechanisms such as Trusted Types, Cross-Origin Resource Policy or Cross-Origin-Opener Policy have not seen any widespread adoption as of yet.

Similarly, convenience features such as the Reporting API, Network Error Logging and the Clear-Site-Data header are also still in their infancy and are currently being used by a small number of sites.

Tying it all together

At web scale, the total coverage of opt-in platform security features is currently relatively low. Even the most broadly adopted protections are enabled by less than a quarter of websites, leaving the majority of the web without platform safeguards against common security issues; more recent security mechanisms, such as Content Security Policy or Referrer Policy, are enabled by less than 5% of websites.

It is important to note, however, that the adoption of these mechanisms is skewed towards larger web applications which frequently handle more sensitive user data. The developers of these sites more frequently invest in improving their web defenses, including enabling a range of protections against common vulnerabilities; tools such as Mozilla Observatory and Security Headers can provide a useful checklist of web available security features.

If your web application handles sensitive user data, consider enabling the security mechanisms outlined in this section to protect your users and make the web safer.